Introduction

Across Europe, the official letter remains the default instrument for notices, decisions, and service of rights. The habit is not irrational: statutes often name “registered letter,” many residents still need paper options, and identity verification has been uneven across borders. Yet the numbers tell a clear story. Letter volumes remain in the billions, delivery performance is inconsistent, and the price of “registered with acknowledgment” keeps climbing. Meanwhile, EU law now recognizes qualified electronic registered delivery with presumptions of integrity, identity, and time‑stamping—turning digital letters into verifiable records that meet official needs.

Why paper persists: statute, inclusion, interoperability

- Statute names the medium. Many sectoral laws still say “registered letter” rather than the technology‑neutral “registered delivery.” Administrators choose paper to remain safe. EU rules now explicitly recognize qualified electronic registered delivery services (QERDS), which enjoy presumptions of integrity, identified sender and recipient, and accuracy of time of sending and receipt (Article 43–44, eIDAS). This provides a lawful digital counterpart to registered post.

- Inclusion obligations remain. Public bodies must serve people who are not ready or able to use digital channels. Even Denmark—the EU’s digital frontrunner—keeps documented exemptions: in Q4 2023, 5.2 million citizens received Digital Post, and 293,212 were exempt. Any transition plan must preserve a paper fallback for such cases.

- Interoperability is mid‑rollout. The European Digital Identity framework (eIDAS 2.0, Regulation (EU) 2024/1183) and the coming EU Digital Identity Wallet aim to standardize cross‑border identity and trust services; Member States are mandated to provide wallets following implementing acts adopted in 2025. The Single Digital Gateway’s Once‑Only Technical System (OOTS) went live to cut re‑keying and reduce administrative burden. These are strong, but still deploying.

The statistics: what paper costs, and how it performs

Volumes and trends

- Germany still handled 10.92 billion letters in 2023, though volumes keep falling.

- France distributed 5.9 billion correspondence items in 2023, down structurally; 5.5 billion in 2024 as the decline continued.

- Across the EU, letter volumes decreased by 5.4% in 2022 (latest consolidated EU statistics).

- Denmark’s mail volumes are down around 90% since 2000; PostNord will end letter delivery by the end of 2025, shifting the universal postal paradigm and underscoring how fast digital became the norm there.

Delivery time and reliability

- Cross‑border letter performance in Europe in 2023 averaged 3.9 days; only 56.6% arrived within three working days and 84.4% within five working days—well below official expectations for time‑critical notices.

What registered paper now costs (examples, domestic, 20 g)

- France (LR + AR): €5.74 (R1) + €1.40 (acknowledgment of receipt) ≈ €7.14.

- Germany (Einschreiben + Rückschein): €0.95 (standard letter) + €2.65 (registered) + €4.85 (return receipt) ≈ €8.45.

- Spain (Carta certificada + Aviso de recibo): €5.29 + €2.66 (incl. VAT) ≈ €7.95.

- Netherlands (Aangetekende brief, online): €10.30.

Costs vary, but the pattern is stable: registering a letter and obtaining proof of receipt can easily run €7–€11 per item before internal handling time.

When public bodies need a signature, acknowledgement of receipt, and archiveable proof, paper forces add‑on fees per letter; these costs scale linearly across thousands of notices.

The inefficiency ledger: where paper undermines policy goals

- Delayed or contested service. When a registered letter is refused or unclaimed, service can still be deemed effective, but disputes follow. By contrast, a qualified electronic registered delivery service produces an immediate, time‑stamped record of acceptance, refusal, or non‑claim, with evidence available no later than the day after the 15‑day window closes (France’s LRE example), reducing ambiguity.

- Inconsistent delivery performance. Averages of 3.9 days cross‑border and just 56.6% in D+3 are incompatible with many procedural deadlines. Digital delivery acknowledges receipt within minutes, with a tamper‑evident log.

- Cost with limited protection. Traditional registered mail can appear “secure,” yet liability is often modest. In Germany, a court required clearer disclosure of the €25 liability limit on ordinary Einschreiben—a reminder that paper registration is not a guarantee of value protection or absolute traceability.

- Operational overhead. Staff print, fold, seal, queue for acceptance, and wait for paper acknowledgments to return—often by post—before updating case files. This produces audit gaps and idle time that a digital audit trail would avoid. (EU postal statistics and regulators consistently document falling letter volumes and network adjustments that create further uncertainty in service levels.)

Although, there is no certain unanimous study on the environmental impact of postal letters globally or locally in the EU, but we can probably expand on the only official study which was done in the UK.

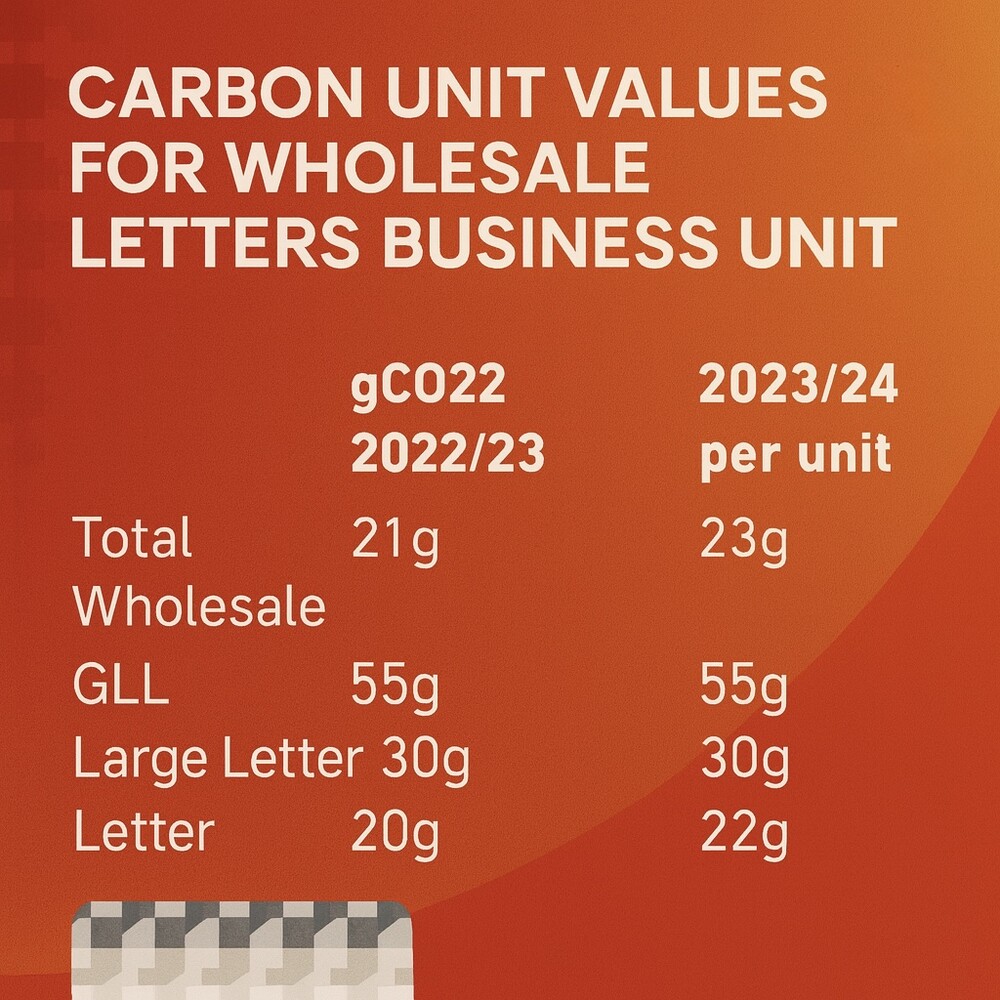

Royal Mail’s wholesale carbon factors (FY 2023/24) estimate ~22 g CO₂e per standard letter, 30 g for a large letter, 55 g for a “GLL” item. Proof: Royal Mail Wholesale “Carbon values” page. Paper letters require paper, printing, transport, and often secondary journeys for return receipts—each item leaves a measurable footprint that compounds at an administrative scale.

Replacing “registered letter” with “registered delivery” in laws and forms is a huge step in bringing a new, secure technology.

The compliant alternative: the official letter, sealed and delivered online

EU law recognizes two levels of electronic registered delivery; qualified services (QERDS) carry legal presumptions that matter for public administration:

- Send → proof of sending and receipt. QERDS confers the presumption that the identified sender sent the data, the identified addressee received it, and the indicated timestamps are accurate.

- Seal → tamper‑evident record. Qualified services protect transmitted data against loss, theft, damage, or unauthorized changes, and bind events to qualified timestamps.

- Verify → recipient identity. Providers must ensure the identification of the addressee before delivery, matching the assurance level needed for the act.

Member States are also deploying the European Digital Identity Wallet, enabling verified identity checks and attribute sharing (e.g., mandates, professional status) across borders, with obligations on availability tied to eIDAS 2.0 implementation.

Evidence that digital works at scale. Denmark’s public sector sent ~62 million Digital Post messages in Q4 2023; 96.6% of residents aged 15+ hold an active eID (MitID). France’s Lettre Recommandée Électronique has the same legal value as paper when requirements are met. Spain centralizes official notices in DEHú, accessible with national eID or eIDAS. These are operational proofs of an official, digital‑first model.

A policy playbook for a paper‑last administration

- Rewrite for technology‑neutral service.

Replace “registered letter” with “registered delivery” in laws and forms; allow paper or qualified electronic delivery.

Proof: admissibility and presumptions under eIDAS Article 43–44; logged, time‑stamped delivery events.

- Anchor identity with the EU Digital Identity Wallet.

Accept wallet‑based identity checks and attributes (e.g., power of attorney) to bind delivery to the right person or legal entity.

Proof: eIDAS 2.0 mandates and Commission guidance on wallet deployment.

- Integrate with the Once‑Only Technical System.

Pull verified data from competent authorities instead of asking citizens to enclose photocopies.

Proof: OOTS live infrastructure aimed at burden reduction and verified cross‑border evidence exchange.

- Preserve inclusion by design.

Maintain a paper channel for exempt residents; use assisted digital points and power‑of‑attorney tooling.

Proof: Denmark’s exemption mechanism and documented adoption metrics for Digital Post.

- Publish service‑level and cost metrics.

Track D+1/D+3 rates and delivery acknowledgments; compare per‑letter cost for registered mail versus QERDS.

Proof: IPC quality benchmarks show baseline mail performance; national tariffs show true all‑in costs.

Conclusion

The official letter is not going away; it is becoming verifiable by default. The evidence is unambiguous: paper is slower, costlier, and harder to audit at scale. EU trust‑service law now equips administrations with a compliant digital replacement that preserves formality, a letter on a digital letterhead, sealed, delivered, verified, and archived with a time‑stamped audit trail. Moving from paper‑first to proof‑first protects due process, reduces disputes, and lowers the total cost of serving rights.

Letro is a secure end-to-end encrypted #FormalCommunication platform designed for mobile and computer. To get more information, Request a demo.

Safe‑claims note

Legally recognized delivery options are available in many regions; confirm local requirements and internal policies before switching critical workflows.